A Study of Uniswap On-Chain Voting: Implications for Power, Apathy, and Evolution

Author: Chao Source: X, @chaowxyz

It should be a decentralized utopia, but data reveals a digital oligarchy controlled by the 1%. We reviewed all on-chain voting on Uniswap over the past four years and uncovered the shocking truth behind Uniswap's governance utopia.

In November 2021, Uniswap, the decentralized finance giant, launched a highly anticipated governance mechanism: a digital democracy system where UNI token holders collectively decide the future of the platform. It paints a tantalizing vision: a pure democratic utopia with no CEO, no board of directors, and power fully and transparently vested in token holders.

However, an in-depth, four-year investigation of the Uniswap Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO)—a detailed quantitative analysis based on 21,791 voters, 68 governance proposals, and 57,884 delegation events—revealed a surprising reality: digital democracy has evolved in practice into a highly concentrated digital oligarchy, and delegation mechanisms intended to improve governance may have the opposite effect, exacerbating inequality and inhibiting participation.

This research not only reveals the complexities of digital governance but also challenges many of our fundamental assumptions about decentralized self-governance, offering profound insights into the future of cryptocurrency and even traditional democracy. It's not a romantic tale of pure democracy, but an epic story about how humanity organizes itself with new tools, balancing efficiency and fairness.

1. The Cold Judgment of Digital Oligarchy

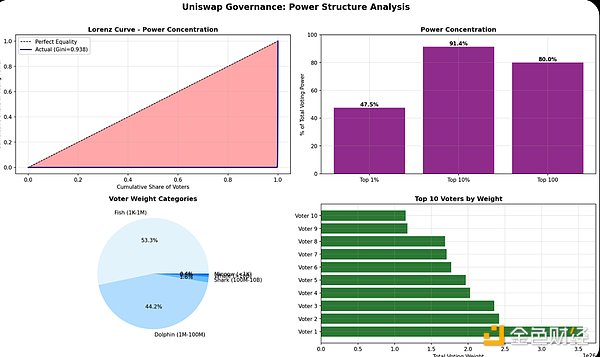

The judgment of data is ruthless. The average Gini coefficient of Uniswap governance is as high as 0.938, which is more unequal than the wealth distribution of almost any country on the planet. The facts are staggering:

• The top 1% of voters control an average of 47.5% of the voting power, and in some extreme proposals it can reach as high as 99.97%.

• The top 10% of voters steadily control 91.4% of decision-making power, making the vast majority of token holders powerless in the decision-making process.

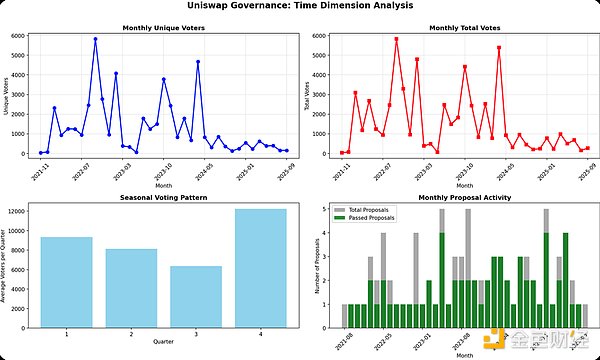

The power structure of Uniswap’s on-chain governance

This concentration of power is not accidental; it's the natural manifestation of token-weighted governance systems in practice. It's accompanied by alarmingly low participation: over four years, the median voter has cast only one vote, while the ten most active voters have voted an average of 54 times each. Monthly participation has plummeted 61% from its peak in 2022-2023, signaling an existential threat to governance legitimacy. We're approaching a point where fewer than 200 people may routinely decide the fate of a multi-billion dollar protocol.

2. “Consensus Theater”: Apathy is more dangerous than opposition

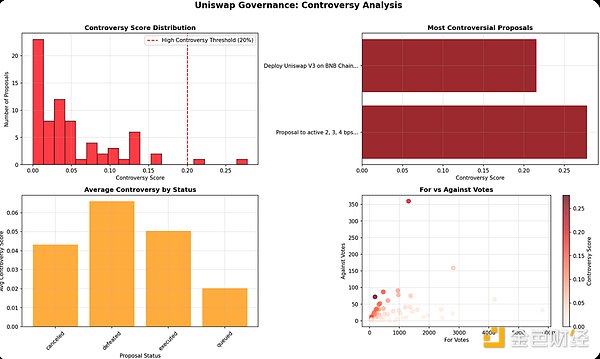

Despite this high concentration of power, Uniswap’s proposal success rate is as high as 92.6%.

It must be acknowledged that most proposals undergo community forum discussion and off-chain voting via Snapshot's "consensus check" before being voted on on-chain. This "consensus-based" mechanism is one of the reasons for its efficiency and high consensus. However, on-chain data still reveals a deeper problem:

- 94.2% of voters are loyal "supporters", with an average support rate of 96.8%.

- 100% of proposal failures are due to failure to reach the minimum voting weight threshold, not majority opposition.

Analysis of the controversial nature of the proposal

Meaningful dissent was exceptionally rare, with only two proposals facing more than 20% of the vote against them. Proposals failed not because of opposition but because of apathy—all five failed proposals failed due to a lack of a quorum, not majority opposition. This reveals a profound truth: the true enemy of democracy, whether digital or traditional, is not disagreement but the apathy of its participants. Convincing people that you are right is less effective than convincing them that they care enough to participate.

3. The Hidden Structure of Power and the Voter Ecosystem

Uniswap’s governance is not a single, flat structure, but a nested and intricate ecosystem.

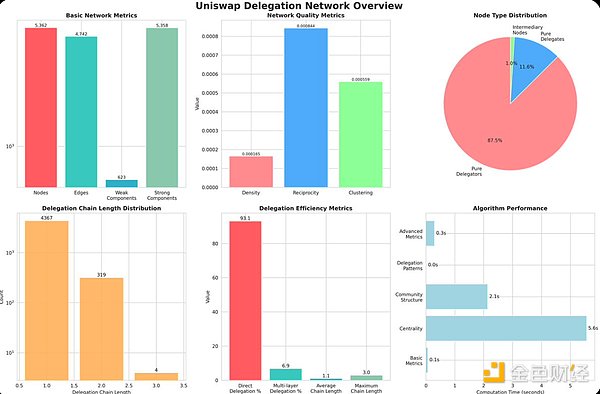

Through network analysis, we uncovered a shadow governance structure operating through delegation. The 5,833 delegation events formed a complex network, but it was highly fragmented, with 623 weakly connected components, forming an archipelagic governance system—islands of dispersed influence rather than a unified democratic system.

At the same time, the network's evolution exhibits a "rich get richer" pattern: 85% of new delegations flow to existing large agents, and the top agents' positions have remained stable for 3.8 years. Its distinctive "star-shaped structure" (87.5% are pure delegators and 11.6% are pure delegates) also clearly outlines the distribution of power around a few central nodes.

Voting Delegate Network Analysis

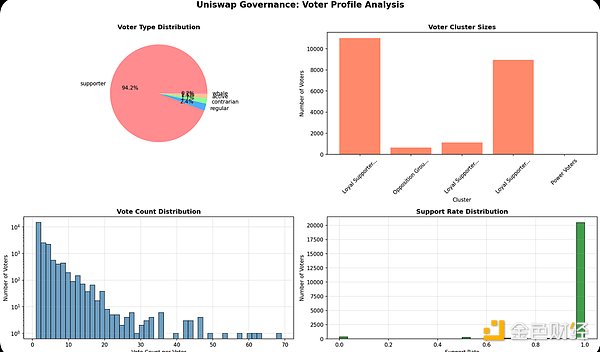

A deeper analysis also identifies different typical types of voters, which constitute Uniswap’s **“Five-Tier Voter Ecosystem**”:

• Whale voters (0.8%): They have extremely high weight, participate infrequently, but have the ability to decide the outcome instantly.

• Active governors (3.2%): They have high weight and high frequency of participation, and are the backbone of governance.

• Institutional participants (1.5%): medium to high weight, selective participation.

• Technical experts (4.1%): medium weight, focused on technical proposals.

• Followers (15.8%): low weight, follow the mainstream.

• Silents (74.6%): Very low weight, minimal participation, representing untapped governance potential.

portraits of voters

These different tiers of voters operate with their own incentives, information levels, and participation patterns. Interestingly, voter lifecycle analysis shows that while voters become more independent with experience, they also tend to delegate more—which explains why experienced participants reduce their direct voting. Furthermore, different types of proposals exhibit distinct power structures: technology deployment proposals have the highest concentration of power (Gini coefficient approximately 0.997), while governance reform proposals have the lowest (Gini coefficient between 0.78 and 0.92). This suggests that Uniswap actually operates "four distinct governance systems" depending on the type of decision.

4. The Commission Paradox: The Backlash of Well-Intentioned Design

Yet, above all these findings lies an even more shocking plot twist: the very system of delegation that aims to democratize governance may be making matters worse.

Delegation mechanisms are widely considered a solution to the problem of token holder laziness. In theory, they should increase participation, improve decision-making quality, and reduce inequality by allowing token holders to delegate voting power to experts or community leaders. While this sounds promising, the data tells a different story.

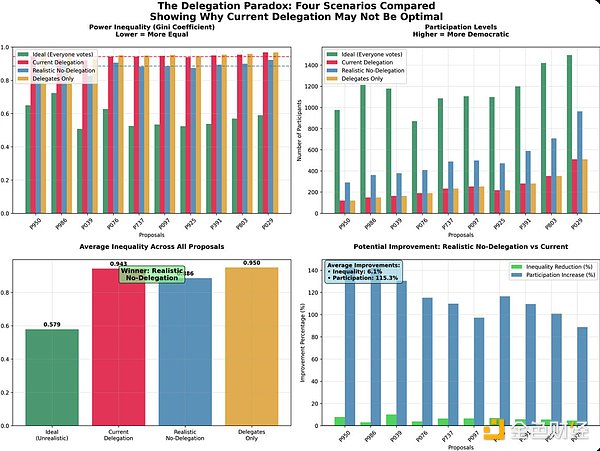

To understand the true impact of delegation, think of these four scenarios as four simulated reruns of the same vote, each time changing a key variable:

Scenario 1: Ideal Democracy (theoretical benchmark) assumes that all token holders vote in person. This represents the theoretical upper limit of the most democratic and equal scenario.

Scenario 2: Current status quo (realistic benchmark) refers to what actually happens: some people vote directly, while others entrust their votes to "representatives" to vote.

Scenario 3: Reality Without Delegation (Key Comparison) This is a key thought experiment: if delegation is disabled, the original group of "delegates" can only vote with their own votes. At the same time, let's assume that 10% of ordinary people who originally chose to delegate are activated and decide to vote in person. This represents the most realistic alternative scenario.

Scenario 4: Delegate-only Voting (Minimal Baseline) assumes that only the currently active group of "delegates" are voting, and they can only use their own tokens, with no delegated votes at all. This represents the lower bound for participation.

• Compared to the real no-delegation system, the current delegation system increases inequality by 6.6% (the average Gini coefficient rises from 0.881 to 0.943).

• Compared to a real-world undelegated system, the delegated system reduces the number of participants by 88% (267 participants per proposal vs. 503 on average).

• All 10 tested proposals showed the same pattern, verifying the 100% consistency of this finding.

This is where the delegation paradox arises: the delegation system simultaneously reduces equality and participation in governance.

Why does this happen? The root cause of the paradox lies in a misunderstanding of human behavior. Conventional wisdom suggests that delegation increases participation through representation, but the reality is:

1. Delegation concentrates power: It concentrates the voting power of multiple token holders into the hands of a few delegates.

2. Reduced number of active participants: Tens of thousands of delegators may end up being represented by only a few hundred active delegators.

3. Create artificial scarcity: There are only a limited number of “trusted” delegators.

4. Inhibition of direct participation: The delegation mechanism creates a psychological effect in which people believe that “someone else will handle it”, thereby inhibiting their willingness to participate directly.

In a real-world non-delegated system, delegators will still vote with their tokens, while some token holders who would otherwise delegate will choose to vote directly. The end result will be more participants and more decentralized power. A system designed to democratize governance may actually have the opposite effect.

5. The Dynamic Evolution of Democracy: Self-Regulation of Oligarchy and a Ray of Hope

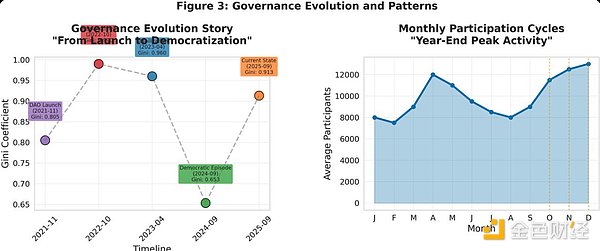

Despite extreme inequality and the delegation paradox, this study also found an encouraging trend: Uniswap is gradually moving towards democratization. Over 3.8 years, the average Gini coefficient dropped from a peak of 0.990 in 2022 to 0.913 in 2025, achieving 8.1% democratization, while the proposal success rate remained above 77%.

The coefficient change in September 2024 was caused by a special proposal and does not represent the overall situation for the whole year of 2024.

This suggests that token-weighted systems have the inherent potential to naturally move toward greater equality through learning and evolution without formal rule changes. While perfect blockchain democracy may be an unattainable utopia, digital oligarchy is not permanent and may represent a transitional stage toward more democratic governance. (Important note: The data used in this comparison is simulated data based on actual voting on existing proposals and reasonable assumptions. It is intended to provide trend insights but is not a true representation of reality. Its modeling assumptions should be considered when interpreting it.)

VI. Profound Implications for Future Governance and the Path Forward

Taking all of these findings into account, Uniswap's governance model can be described as an efficient and stable, yet highly elitist "Plutocratic Republic." While it excels at driving technical iteration and fund management, it falls significantly short of the democratic ideals of a decentralized community.

Uniswap's governance structure, a blend of oligarchic efficiency, broad legitimacy, economic coherence, and the ability to evolve, bears resemblance to the historical Venetian Republic. The Venetian Republic endured for millennia by balancing these forces, and perhaps Uniswap has inadvertently recreated a time-tested governance model—not pure democracy, but a functional democracy that works in practice.

However, they are forcing the industry to rethink:

- Is delegation justified as the default mechanism? It may not be a universal solution, but rather a "prescription drug" that needs to be used with caution. Don't blindly assume that delegation improves governance outcomes; instead, verify its effectiveness through empirical analysis. Don't blindly assume that delegation improves governance outcomes; instead, verify its effectiveness through empirical analysis.

- Should the optimization direction of DAO governance shift from "optimizing delegation" to "incentivizing direct participation"?

- Should we design new governance modules, such as liquid democracy, quadratic voting, etc., to balance the systemic flaws of the existing delegation system?

The story of Uniswap isn't a failure, but rather a valuable example, rich with real-world data and lessons learned. However, the hope is that these systems can evolve, improve, and become more democratized. We're not stuck with the first version of digital governance; we can learn, adapt, and build better systems.

Despite its inequalities, Uniswap’s governance has achieved remarkable success: a 91% proposal success rate, continued democratic evolution, broad legitimacy, and alignment of economic interests. This may not be the perfect democracy we imagine, but it may be a more valuable functional democracy.

Uniswap's governance experiment provides an unparalleled real-world laboratory, allowing us to study, with complete transparency, how human society organizes under new tools for collective decision-making. Digital oligarchy is not a design flaw, but rather a feature of how humans naturally organize themselves in the face of new tools. Understanding and adapting to this reality, rather than fighting it, may be the key to building the next generation of organizations and governance systems. The future of governance, both digital and traditional, will be built on the valuable lessons we learn today from these early experiments in decentralized democracy.

You May Also Like

Ethereum Foundation Converts $4.5M ETH to Stablecoins

Central Bank of Nigeria set to work on crypto regulation framework with the SEC, governor confirms