Model.fit is More Complex Than it Looks

One of the classic ML interview questions is: There is a closed-form solution for linear regression. Why don’t we just calculate it directly?

And the equally classic answer is: Well, it’s computationally unstable.

But why, actually? Here I’ll try to answer the question in as much detail as possible. We’ll dive into numerical linear algebra, how numbers are represented on a computer and the quirks that come with that, and finally find ways to avoid problems you’ll never see on paper.

Is it Really a Problem?

Being good researchers, we can run an experiment ourselves. Let’s take the classical iris dataset, and solve it in the classical way, and using the textbook formula (which is very satisfying to derive ourself!), and see how the results differ from model.fit.

import numpy as np from sklearn import datasets from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression # 1. Load the iris dataset X, y = datasets.load_iris(return_X_y=True) # 2. Naive normal-equation solution: beta = (X^T X)^(-1) X^T y XTX = X.T @ X XTX_inv = np.linalg.inv(XTX) XTy = X.T @ y beta_naive = XTX_inv @ XTy print("\\nNaive solution coefficients") print(beta_naive) # 3. Sklearn LinearRegression with fit_intercept=False linreg = LinearRegression(fit_intercept=False) linreg.fit(X, y) beta_sklearn = linreg.coef_ print("\\nsklearn LinearRegression coefficients") print(beta_sklearn) diff = beta_naive - beta_sklearn l2_distance = np.linalg.norm(diff) print(f"\\nL2 distance between coefficient vectors: {l2_distance:.12e}") ---Res--- Naive solution coefficients [-0.0844926 -0.02356211 0.22487123 0.59972247] sklearn LinearRegression coefficients [-0.0844926 -0.02356211 0.22487123 0.59972247] L2 distance between coefficient vectors: 2.097728993839e-14

Looking good right, our solution virtually matches model.fit.So…shipping to prod?

Now, let’s cover this example with the tiny 7x7 feature matrix.

import numpy as np from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression def hilbert(n: int) -> np.ndarray: """ Create an n x n Hilbert matrix H where H[i, j] = 1 / (i + j - 1) with 1-based indices. """ i = np.arange(1, n + 1) j = np.arange(1, n + 1) H = 1.0 / (i[:, None] + j[None, :] - 1.0) return H # Example for n = 7 n = 7 X = hilbert(n) # Design matrix y = np.arange(1, n + 1, dtype=float) # Mock target [1, 2, ..., n] # Common pieces XTX = X.T @ X XTy = X.T @ y # 1. Naive normal-equation solution: beta = (X^T X)^(-1) X^T y XTX_inv = np.linalg.inv(XTX) beta_naive = XTX_inv @ XTy print("\\nNaive solution coefficients") print(beta_naive) # 2. Solve-based normal-equation solution: solve (X^T X) beta = X^T y beta_solve = np.linalg.solve(XTX, XTy) print("\\nSolve-based solution coefficients") print(beta_solve) # 3. Sklearn LinearRegression with fit_intercept=False linreg = LinearRegression(fit_intercept=False) linreg.fit(X, y) beta_sklearn = linreg.coef_ print("\\nsklearn LinearRegression coefficients") print(beta_sklearn) # --- Distances between coefficient vectors --- diff_naive_solve = beta_naive - beta_solve diff_naive_sklearn = beta_naive - beta_sklearn diff_solve_sklearn = beta_solve - beta_sklearn l2_naive_solve = np.linalg.norm(diff_naive_solve) l2_naive_sklearn = np.linalg.norm(diff_naive_sklearn) l2_solve_sklearn = np.linalg.norm(diff_solve_sklearn) print(f"\\nL2 distance (naive vs solve): {l2_naive_solve:.12e}") print(f"L2 distance (naive vs sklearn): {l2_naive_sklearn:.12e}") print(f"L2 distance (solve vs sklearn): {l2_solve_sklearn:.12e}") # --- MAE of predictions vs true y for all three methods --- y_pred_naive = X @ beta_naive y_pred_solve = X @ beta_solve y_pred_sklearn = X @ beta_sklearn mae_naive = np.mean(np.abs(y - y_pred_naive)) mae_solve = np.mean(np.abs(y - y_pred_solve)) mae_sklearn = np.mean(np.abs(y - y_pred_sklearn)) print(f"\\nNaive solution MAE vs y: {mae_naive:.12e}") print(f"Solve-based solution MAE vs y: {mae_solve:.12e}") print(f"sklearn solution MAE vs y: {mae_sklearn:.12e}") ---Res--- Naive solution coefficients [ 3.8463125e+03 -1.5819000e+05 1.5530080e+06 -6.1370240e+06 1.1418752e+07 -1.0001408e+07 3.3247360e+06] Solve-based solution coefficients [ 3.88348009e+03 -1.58250309e+05 1.55279127e+06 -6.13663712e+06 1.14186093e+07 -1.00013054e+07 3.32477070e+06] sklearn LinearRegression coefficients [ 3.43000002e+02 -1.61280001e+04 1.77660001e+05 -7.72800003e+05 1.55925001e+06 -1.46361600e+06 5.16516001e+05] L2 distance (naive vs solve): 4.834953907475e+02 L2 distance (naive vs sklearn): 1.444563762549e+07 L2 distance (solve vs sklearn): 1.444532262528e+07 Naive solution MAE vs y: 1.491518080128e+01 Solve-based solution MAE vs y: 1.401901577732e-02 sklearn solution MAE vs y: 2.078845032624e-11

Something is very wrong now. The solutions are far from each other, and the MAE has skyrocketed. Moreover, I added another method. Instead of inverting and multiplying matrices, np.linalg.solve was used.

The naive inverse is terrible; np.linalg.solve is much better but still noticeably worse than the SVD-based solver used inside sklearn.

In the realm of numerical linear algebra, inverting matrices is a nightmare.

\

Aside. One more reason not to do it.

Someone might say that the reason is because the matrices are huge. Imagine you have a titanic dataset that is hard to fit in memory. True, but here is the thing:

You operate with feature-by-feature matrices. Computing X.T @ Xor X.T @ y can be done in batches … If this algorithm actually worked, it would be better than doing iterations. But it doesn’t.

What is Going on?

The matrix we used in the second example is a Hilbert matrix.

And its problem is that it’s ill-conditioned. For these types of matrices solving the equations like $Ax= b$ becomes numerically impossible.

SVD

There is a cool fact that any matrix (aka linear operator) can be written as the composition of a rotation, a scaling, and another rotation (rotations may include reflections). In math words:

where

Uis an orthogonal matrixU.T == U.inverse,Vis an orthogonal matrix,

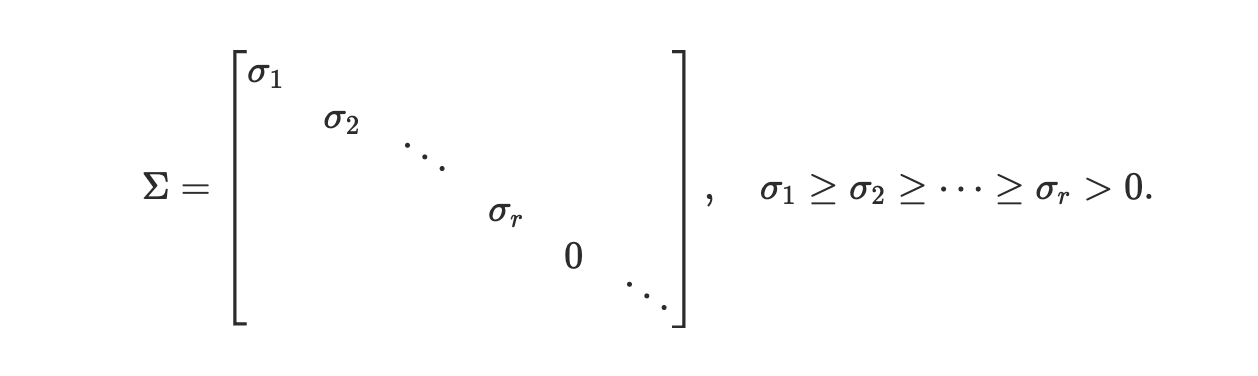

Sigma is a diagonal matrix with non-negative entries:

The scaled axes are called singular vectors and the scaling values — singular values.

By the way, LinearRegression.fit uses this under the hood (via an SVD-based least-squares solver).

It computes the SVD for X, does some variable substitution, in which the solution is just:

Understanding SVD and this decomposition help us get the matrix norm, which is the key to instability.

Matrix Norm

By definition, it is the maximum amplification of this operator applied to a sphere. With the SVD decomposition, you can see that for the 2-norm this is just the largest singular value.

Aside.

In what follows we use the L2 norm. The expressions and equalities below are written specifically for this norm; if you chose a different norm, some of the formulas would change.

Inverse Matrix

The backward operator. You may notice that the norm is equal to 1/min(singular(A)).

If you shrink something a lot, you must scale it a lot to get back to the original size.

Condition Number

Finally, the root of all evils in numerical linear algebra, the condition number.

It is important because it appears in a fundamental inequality that describes how the relative error in the solution behaves when the matrix, the right-hand side, or the solution are perturbed.

We start with a linear system

and a perturbed right-hand side

Then, for any consistent norm, the relative change in the solution is bounded by

Thus, the relative error in the solution is proportional to the condition number. If the condition number is large, the solution may change dramatically, regardless of how accurate the solution method itself is.

For example, if norm(b) == 1; norm(delta_b) == 1e-16 and cond(A) = 1e16, then the difference between the perturbed solution and the “true” solution can be on the same order as the solution itself.

In other words, we can end up with a completely different solution!

Bad in theory, impossible in practice

There are many different sources of error: measurement errors, conversion errors, rounding errors. They are fairly random and usually hidden from us, making them hard to analyse. But there is one important source on our side: floating-point arithmetic.

Floating points

A quick recap: computers represent real numbers in floating-point format. The bits are split between the mantissa (significand) and the exponent.

If you look more closely at the IEEE 754 standard, you’ll notice that the distance between two consecutive representable numbers roughly doubles as the absolute value increases. Each time the exponent increases by one, the spacing between neighbouring numbers doubles, so in terms of absolute spacing you effectively “lose” one bit of precision.

You might have heard the term machine epsilon. It’s about 1e-16, and it is exactly the distance between 1.0 and the next larger representable float.

We can think of the spacing like this: for a number x, the distance to the next representable number (often called one ulp(x)) is roughly

So the bigger abs(x) is, the bigger the gap between neighbouring floats.

You can try it yourself. Just compare 1e16 + 1 == 1e16 and see that this is true.

Can you see now what is happening with inverting matrix?

Why Our Solution Fails

So, solving Ax = b can be reduced, using the SVD, to computing

where y and c are the vectors x and b expressed in the orthogonal bases from the SVD.

If the condition number is, say, 1e17, then in this sum the contributions corresponding to the largest singular values are almost completely drowned out. Numerically, they get added to much larger terms and make no visible difference in floating-point arithmetic.

This is exactly what happens in the example with the Hilbert matrix.

You might reasonably ask: if this is such a fundamental problem, why do the library functions still work?

The reason is that our naive solution has another fundamental flaw.

Quadratic problem

As mentioned above, there is an inequality that is independent of the particular solver. It is a purely geometric property and depends only on the sizes of the numbers involved.

So why does the model.fit approach still work?

Because there is another important fact about matrices:

The proof is quite straightforward and actually pleasant to work through. We will prove an even more general statement:

This is already the SVD of A.T @ A. Moreover, since A^T @ A is symmetric, its left and right singular vectors coincide, so its orthogonal factor is the same on both sides.

And since Sigma is diagonal, squaring it is just squaring singular values.

What does this mean in practice? If a feature matrix X has cond(X) ~= 1e8, things are still relatively okay: we may have some sensitivity to errors, but we’re not yet completely destroying the information in floating-point arithmetic.

However, if we compute X.T @ X, its condition number becomes roughly cond(X)**2, so in this example about 1e16. At that point, the computer cannot meaningfully distinguish the contribution of terms involving the smallest singular values from the much larger ones — when they are added together, they just “disappear” into the high-order part of the number. So the calculations become numerically unreliable.

Indeed, let’s look at our Hilbert matrix:

H = hilbert(7) HtH = H.T @ H print(np.linalg.cond(H)) print(np.linalg.cond(HtH)) ---Res--- 475367356.57163125 1.3246802768955794e+17

You can see how the condition number of H.T @ H explodes to around 1e17. At this level, we should fully expect serious loss of accuracy in our results.

Aside. Built-in solvers are smart enough to avoid this.

While manually inverting a matrix, or even using linalg.solve in a naive way, can be numerically unstable, something like model.fit(…) usually goes a step further.

Under the hood it often uses an SVD. If it detects singular values on the order of machine epsilon, it simply sets them to zero, effectively removing those directions from the solution space. It then solves a well-conditioned problem in this reduced subspace and, among all possible solutions, returns the one with the smallest norm.

What can we do?

Well, use standard solver. But there are some other approaches that are worth mentioning.

Normalising. Sometimes a large condition number is simply due to very different scales of the features. Standardising them is a good way to reduce the condition number and make life easier for floating-point arithmetic.

However, this does not help with linearly dependent features.

Another approach is L2 regularisation. Besides encouraging smaller coefficients and introducing some bias, it also acts as a kind of “conditioner” for the problem.

If you write down the solution to the least-squares problem by computing the gradient and setting it to zero, you get

This is still a linear system, so everything we said above about conditioning applies. But the singular values of the matrix X.T @ X + alpha * I are sigma_i**2 + alpha, where sigma_i are the singular values of X. Its condition number is

Adding alpha shifts the smallest singular value away from zero, which makes this ratio smaller, so the matrix becomes better conditioned and the computations more stable. Tricks of this kind are closely related to what is called preconditioning.

And finally, we can use iterative methods — SGD, Adam, and all the other things deep learning folks love. These methods never explicitly invert a matrix; they only use matrix–vector products and the gradient, so there is no direct inversion step. They are typically more stable in that sense, but often too slow in practice and usually worse than a good built-in direct solver.

Want to Know More?

This has just been a showcase of numerical linear algebra and a bit of interval arithmetic.

Frankly, I haven’t found a really good YouTube course on this topic, so I can only recommend a couple of books:

- Accuracy and Stability of Numerical Algorithms – Nicholas J. Higham (SIAM)

- Introduction to Interval Analysis – Moore, Kearfott, and Cloud (SIAM)

\

You May Also Like

Tezos (XTZ) Price Prediction 2025, 2026-2030

Top 3 Cryptos to Invest in Before a Full-Blown Meme Coin Season